I never thought I was interested in history. In Scotland, we weren't even taught our own history in high school. Having moved from Yorkshire to Scotland in my early teens, I didn't understand why some people treated me with contempt. Sure, mocking a northern accent felt like typical teenage behaviour, and I was certainly a gregarious and confident young teen initially, but I couldn't grasp why there was so much resentment toward the English. The duality of the people of Scotland, as both colonised and colonisers, is something I began to unravel many years later through the lens of food.

Like many, I had never heard about publicly funded British Restaurants that popped up during and after wartime in the UK until I read I Dream of Canteens by Rebecca May Johnson and her subsequent piece, The Canteen, which is published in the wonderful London Feeds Itself, a book edited by Jonathan Nunn which explores the city and its people's relationship to place through food.

Because of this growing curiosity, in February this year, I attended a conference-style event hosted by Nourish Scotland. It was entitled Public Diners—Infrastructure of a Good Food Nation. The day explored the potential to bring back subsidised restaurants and explore food as a public good, as well as the ideal infrastructure that would support this.

Working in food often fuses the personal with the political, and the timing of this event was significant. I'd been made redundant from my Assistant Manager role at Locavore CIC in January, followed by the company's insolvency and the loss of my Trading Coordinator role two days before the event. Losing this position and my anticipated income was a nasty shock. That week, a new friend asked me if I was heartbroken, and I replied, 'Yes, but not broken'.

Walking up the steps to the registration table at Central Hall in Tollcross, I felt excited and reinvigorated. It was the first time since the Covid outbreak that I had seen such a big food justice event organised in Scotland. As I reached the table and saw the participants' names laid out as badges, I felt heat rise and realised I was about to start crying. I knew so many names on that table—people I had worked with and volunteered with at film festivals, community gardens, pop-up mobile kitchens, and farmers and food producers. Some had cooked for me the evening I found out my mum had died. Even my landlord was cooking the communal lunch for the day! I hadn't seen these people in ages, at least not all together in one space.

This small, entangled network's familiarity is a testament to a thriving food movement in Scotland. Finding community often means being found in return, making reinvention—or anonymity—a challenge. After all, we are always changing and evolving. As I fought back tears and hung my coat on the rack, I was greeted by a few more familiar faces. At that moment, the coat stand began to topple, and like a scene from a sitcom, we all rushed to prevent it from falling on anyone—the shock of this moment helped ground me immediately in my surroundings.

It was a wonderful day, a mixture of talks from academics, including Bryce Evans and the Nourish Scotland project planning team, brainstorming different elements of what should and could constitute a public diner, from the menu and sourcing to the interior and locations. There were also sessions run in the Unconference format, including a wonderful session from radical dietician and poet Lou Aphramor, and I found myself unexpectedly ending up hosting a session on 'dignity in sourcing'!

At the end of the day, Nourish announced they were seeking volunteers to help with archival research of the previous restaurants, as very little was known about them. A few days later, I expressed my interest. The research project is supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. Since then, I've had training on oral history, been given access to the British Newspaper Archives, and participated in a few other volunteer sessions. The project also gave me an opportunity to meet Lindsay Middleton and Katie Revell, people whose work in food I've been following for a while but had never met! I started editing this piece whilst on a train down to London to visit the National Archives and the Imperial War Museum for further research.

Recently, Nourish published their report on their vision for a public diners' infrastructure, which was also featured in The Guardian:

A forthcoming report entitled Public diners: the idea whose time has come, by food policy NGO Nourish Scotland, marks the beginning of a campaign to introduce restaurants as a new piece of national infrastructure, a call backed by politicians and experts.

A public diner, according to the report, is a state-subsidised eatery serving quality and ethically produced food at affordable prices. Crucially, says Nourish Scotland, they are neither charity nor a treat, but rather everyday eating places for entire communities to access.

In this article, I’m going to share a little of the process of trawling through old newspaper archives to try to find out which public diners existed in Edinburgh and when, and share a few interesting pieces I’ve discovered so far. Overall, I’d hoped to uncover more about the menus, sourcing, and supply chains of public diners in Scotland.

The Process of Mapping Restaurants in Edinburgh

I started with the knowledge that there were around 15 such restaurants at one point in Edinburgh, but I didn't know where they were located or what they were called. Using various search terms, I tried to find details of these establishments. I found in the British Newspaper Archive that ‘civic restaurants’ was a more effective search term for the Scottish establishments than ‘British restaurants’. Still, it was when I stumbled upon a notice of closure for a group of Edinburgh restaurants that I could use the names and locations to trace further information about their opening and closing dates. It was quite an addictive process, especially when I realised that many former venues were very close to where I live, and some still function as food businesses or food-adjacent social enterprises.

Thus far, I have been unable to track down a restaurant that apparently was situated on Gorgie Road, which would have been the closest to where I live. I've not found anything about this venue apart from the fact that it existed and that it closed on November 30, 1945.

British Restaurants in Edinburgh Map

Here's a copy of the Edinburgh Civic Restaurants map locations, which is a work in progress... The locations marked in green were central cooking depots, training centres or administrative hubs for the publicly subsidised restaurants.

Bon Accord Gossip

Think It Out!

Aberdeen Evening Express, Tuesday August 26, 1941

“Sit down and put on your thinking cap. There are prizes of two guineas and one guinea waiting for bright ideas in giving a name to the city's first community restaurant to be opened at Castlehill. It is not a novel idea. Similar competitions have been run in other cities. Perhaps you would like to know some of the winning efforts there. At Dundee the name "Tuck Inn" got the prize, while in Edinburgh "Neebors' Tryst" was selected as the best name. In another town one competitor had only to write "Churchill" to win a prize. But not this way. I will give you some inkling as to how to go about it, but if you're not above taking a hint I can tell you that in the opinion of the committee, who will select the best Aberdeen efforts. "Tuck Inn" and "Neebors' Tryst" would not have won you prizes. "Tuck Inn" is a clever play on words and "Neebors' Tryst" has a friendly atmosphere about it, but from what I gather something a little more dignified will catch the local adjudicators' eyes. You can all enter for the competition. Have your entries in the hands of the Town Clerk on or before September 8.”

This competition announcement was a fun find, especially as a fan of food puns. In Aberdeen, it seems that naming a restaurant was a serious business with real guineas at stake. The Aberdeen committee seemed to have loftier ambitions for their restaurant than the neighbourly charm of Edinburgh's "Neebors' Tryst" or Dundee's "Tuck Inn" —they were hoping for names with gravitas—hoping to emulate air of fine dining, rather than the accessible fun of a community space. I wonder, if you had to enter a competition to name a public restaurant nowadays in your neighbourhood, what would you call it? I loved the name of the Leith restaurant, 'The Laden Creel,' so much that I decided to use it for this piece. It conjures up such an appetising and abundant image of a Scottish coastal diner.

Fare Ye Weel

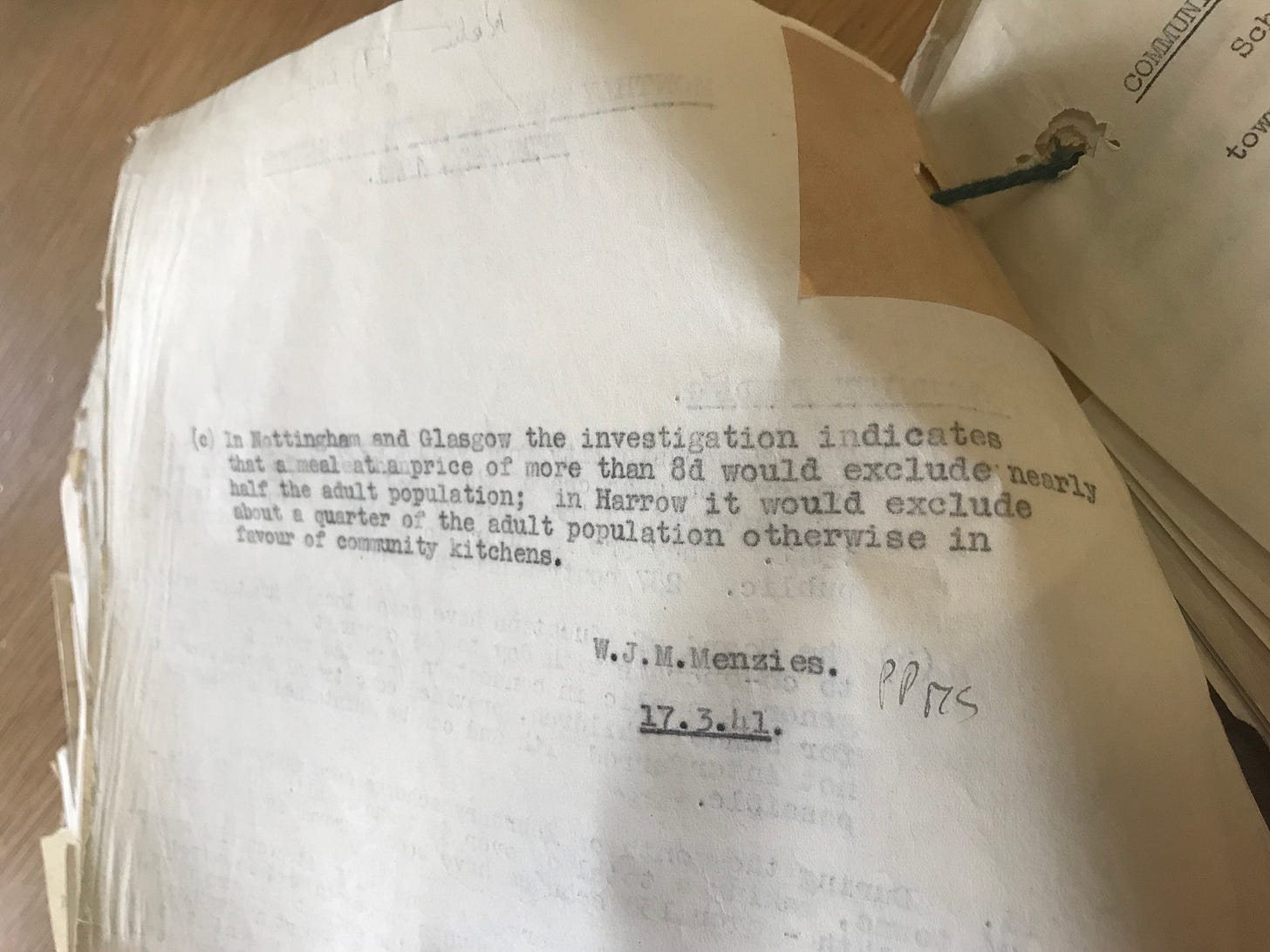

The opening of Edinburgh's Fourth Civic Restaurant at Dalry House combined practicality with a fascinating mix of history. This interesting building— a 17th-century mansion where Charles II once slept now looks slightly out of place building amongst the surrounding row of tenement flats and is just 12 minutes from where I live and even closer to my old workplace in Dalry (an organic zero-waste supermarket which also which used to house a canteen1) Despite its historic setting, the restaurant embraced modern appliances and efficient methods. Fare Ye Weel aimed to serve affordable meals to a working-class community while battling misconceptions that it was just an "emergency soup kitchen." The prices—2d for soup and 6d for a meat dish were affordable to patrons. Although local authorities were able to set their own menus and pricing, there was correspondence in the National Archives at Kew stating that according to investigations into pricing, in Nottingham and Glasgow, any meals set at over 8D would become prohibitive to the community - excluding nearly half the adult population from access, whilst in Harrow meals over 8D would exclude around a quarter of the population who would otherwise be in favour of community kitchens. Not being an economist, it is difficult to translate what cost 8D (8p) would be equivalent to now, but the online calculator 'Measuring Worth' anticipates the cost of 8D in 1941 would range in equivalence from £1.43 to £10.42 in 2023, while the Bank of England Inflation calculator (based on the Consumer Price Index) calculates this amount as currently being equivalent to £3.39.

The Scotsman - Tuesday, 12 August 1941

“Edinburgh's Fourth Civic Restaurant was opened yesterday on the ground floor of Dalry House, a seventeenth-century mansion in the west of the city. It has been christened "Fare Ye Weel". "In the dining room, where there is seating accommodation for about a hundred lunchers, meals will be served every weekday at cheap prices. A plate of soup costs 2 d, a dish of meat 6 d and a portion of pudding 2 d. There is also a second room where tea is served. The premises have been made 'available by the Dalry House Trust, which accommodates the youth clubs of the district under a single roof. The building also houses "Toe H" and contains a chapel. In one of its upper rooms, Charles II slept in 1661. A fine-moulded ceiling commemorates the event. Councillor Donald Munro, who, as chairman of the sub-committee planning the restaurants, presided at the opening ceremony, said that there still seemed to be a great deal of misunderstanding both as to the purposes of the restaurants and the way in which they were run. Too many people, he said, thought they were something in the way of emergency soup kitchens when they were restaurants in the same sense as were other restaurants in the city, but restaurants which performed for the working class districts the important function which the catering industry had performed very ably, and certainly very adequately, for the more well-to-do districts. They were part of the Ministry of Food's plan to make the food resources of the city go round. Bailie R . E . Douglas Chief Magistrate, who opened the new restaurant, said that the success of those in other districts encouraged the Committee to push on and make further plans for the future…The most up-to-date methods and appliances were, he said, employed, and the restaurants were doing much to simplify the work of the housewife (and) provide food for the family…”

Here's a current photo of the building. Delightfully, it currently houses Garvald, a social enterprise that offers people with disabilities the opportunity to participate in creative workshops and paid work experience. This connection is fascinating because Garvald runs a commercial bakery that supplies the community-owned business where I work with popular organic ranges. However, this particular building runs other craft practices under the name of Orwell Arts.

According to other archival research, Dalry House actually used to be gardens - see this video from Historia Lothiana:

From our Turret Window

Edinburgh Evening News, Saturday, 11 October 1941

Descriptions of what we eat are the monopoly of film stars and others similarly situated. What reporters eat is a matter of no moment, but public interest demands that I recount yesterday’s gastronomic adventure. I had rich broth, cold meat, tomato, lettuce, and ‘mashed potato, followed by a generous helping of pudding with custard —all for 10d! When the plates were empty I realised the significance of the name given to the restaurant, “The Laden Creel.” This British Restaurant in North Fort Street, Leith, is not attracting the custom expected, and so a strangely assorted group set out to find the reason why.

“An Amazing Bargain”

One visitor, a connoisseur in fine foods, agreed “it was splendid food and an amazing bargain.” Then we discussed the present and future. Mr David Robertson, former Town Clerk, who recalled that some 50 years ago there was only one restaurant in Princes Street, thought an extension of the British Restaurant movement highly desirable. Mr J. W. Herries thought it strange that while every African village had its community centre, so-called civilisation lacked that amenity. “Many of us are marooned in our homes, and have little contact with our fellows. The British Restaurant is a move in the right direction.” Lady Ruth Balfour paid a tribute to the foresight of the Ministry of Food and the enterprise of the Coronation; “We have more British Restaurants than any other place in Scotland.”

The Neighbours

Councillor J. J. Robertson echoed general opinion when he thought the lack of support could be ascribed to prejudice. “I was desperately hungry when I came in here,” confessed the sturdy Councillor, “and I have had a remarkably good lunch.” Mr Robertson thought they had to get rid of the feeling that a housewife seen entering a British Restaurant would be dubbed by her neighbours as not being a good cook. Tenpence is not the lowest price, so the housewife who would like to defy the neighbours should tell them to go to— “The Laden Creel.”

It was an absolute joy to stumble across this piece as it was the first article I found in which a columnist reviewed a civic restaurant in Edinburgh using a distinctive personality. Having only mainly found opening and closure notices up to this point, I was enamoured to find a piece with a clear comedic undertone, the writer recounting their ‘gastronomic adventure’ and trying to dispel prejudice around dining in such places where diners were sometimes judged as poor cooks. Despite a clear social agenda—highlighting the importance of public dining spaces and the community-building aspects of British Restaurants, it's still tarred with a little haughtiness and casual racism. It's a sign of the times, perhaps, but a time that paved the way for a trend that still persists in the copy of many mainstream food reviewers in the UK2.

Trouble at Neebors’ Tryst

Neebors’ Tryst was the first civic restaurant in the capital. At the time it was a old school site, next to where the Moxy hotel is now situated. As an early model in Scotland it attracted a lot of UK-wide press coverage, fancy artwork, royal visits, and lords and ladies - notably the name 'Balfour’ looms in the Edinburgh press coverage. But for now, I am less interested in the Balfour's visits to eateries (more of that in Part 2)3; instead, I want to share the… other tea, the juicy gossip!

Daily Mirror - Monday 03 March 1941

10d. LUNCH AT THE "NEEBORS' TRYST"

Soup ld., roast beet, potatoes, turnips, 6d.; sponge pudding with custard sauce, 2d.; cup of tea or coffee Id. That is a sample of the 10d. luncheon to be served at The Neebors' Tryst, the name given to the first communal restaurant in Scotland, which is to be opened on Wednesday by Lord Provost Sir Henry Steele. The Tryst is an old school at Fountainbridge, a busy Edinburgh industrial centre. Mural decorations in the dining-room are being done by Mr Douglas Moodie, president of the Society of Scottish Artists, assisted by girl students from Edinburgh College of Art. The restaurant will have seating capacity for 150 people. Three sittings for luncheon are aimed at, and later it is hoped to arrange for morning and evening meals. Plans are being made in co-operation with the Ministry of Food for centres to be opened in other parts of the city.

As the article below states, it seems impossible to run a community space without there being some beef, and here we are - a gendered spat about meat and how women used the space for "smoking and gossiping while their children were allowed to roam all over the place."

In a time where meat was rationed, where resources were scarce, the official thought that the food "should be available only for people such as workers, who cannot get home for their food… a lot of the people who had to be turned away today were far more deserving cases than those women and others who live in the immediate neighbourhood and do not need to come here. We were allowed meat for over 150, and it turned out that was not half enough. Our supply was done within an hour, and soon we had nothing to offer but pudding, beans and bread, and tea."

Interestingly, on our research trip visit to Beamish, we were informed that access to meat due to rationing was harder in cities due to supply chain issues and that rural residents often consumed more due to their proximity to the source. In fact, we were told that despite wartime rationing, male British army officers would often be able to access meat and could consume around 5,000 calories a day! For reference, as a guide the NHS states: an average man needs 2,500kcal a day and an average woman needs 2,000kcal a day.

St Thomas

It took me a wee while to track the exact location of the St Thomas restaurant as the name of the road had changed slightly since the original publication of the articles. But the building of St Thomas is now recognisable as Edinburgh's West End venue 'Ghillie Dhu', a bar and restaurant often used to host ceilidhs, wedding celebrations and musical events. As a venue distinctively showcasing traditional aspects of Scottish culture, it purports to show pride in "celebrating Scotland's larder and strive to showcase some of the finest suppliers from all over the country."

The article below states that the publicly funded venue of the 1940s served over 1,000 meals a day, with the ground floor accommodating 280 people, and it had plans to extend the dining space. At the time of reporting, it stated that Edinburgh's remaining five public restaurants were serving 18,000 meals per week. There are also press reports during this period that celebrate the fact that imported fresh tomatoes were available in some of the Edinburgh venues, which contrasts with the expectation that only tinned tomatoes were accessible at the time. Lunch here appears more expensive than 10 minutes away in Dalry, with a three-course meal costing 1s 3D, though there were snacks such as ham croquettes and chips or galantine and salad available for less. You can imagine my delight while looking at the current Ghillie Dhu offering and discovering it still has ham and cheese croquettes on the menu!

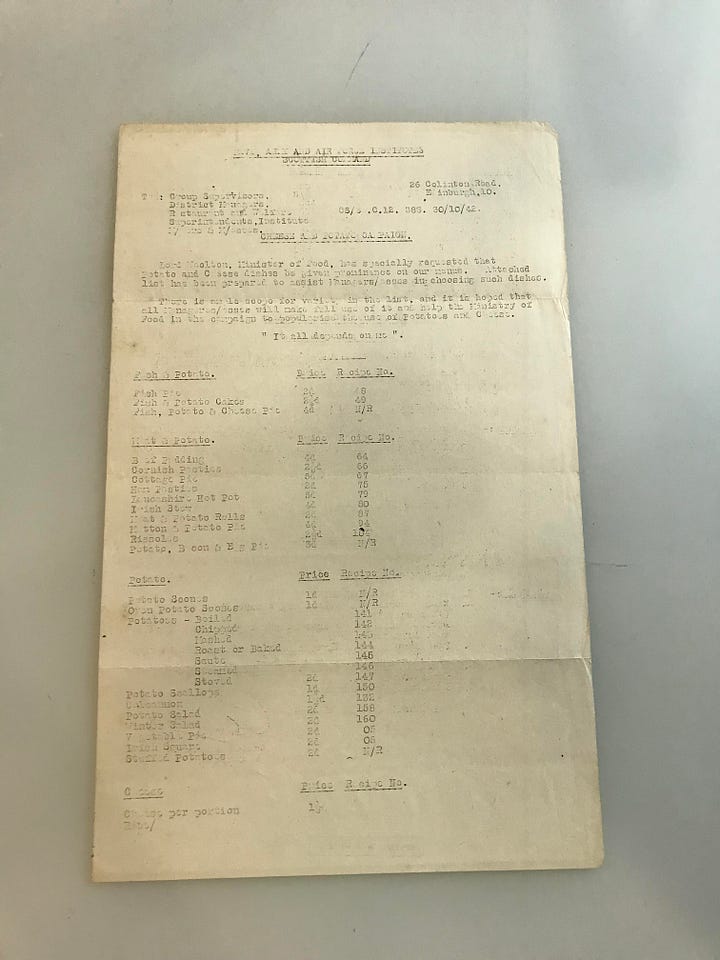

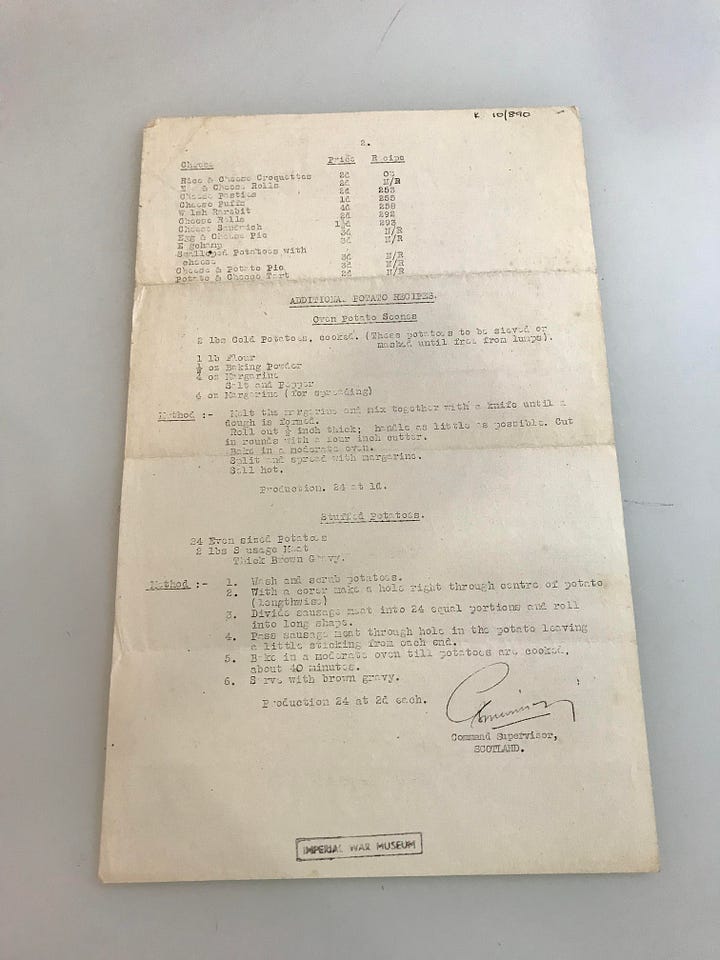

This dish brings to mind one of my favourite discoveries in the Imperial War Museum archive, a memorandum complete with recipes from October 1942 sent to Navy, Army and Air Force Institute group supervisors, district managers, restaurant and welfare superintendents, and institute managers. The memo had a specific request from Lord Woolton, Minister of Food, to give prominence to potato and cheese dishes4 on menus. Details include a serving suggestion of rice and cheese croquettes to be priced at 2D.

Getting hungry for archival research

The above newspaper and archive documents are just a fragment of what I discovered about some of the publicly subsidised diners in Edinburgh. If you have any knowledge about the Gorgie site, or might know anyone who does, please do reach out!

In Part Two, I plan to share some other findings, including discussing the recruitment and training of cooks, Scottish vs. English stereotypes around domesticity, Royal Venison on the menu, a man ‘going to pieces' over the closure of the public restaurants, and the discombobulating experience of researching wartime documentation whilst protesting our complicity in genocide.

But in the meantime…

Further Reading

This was a canteen in spirit as well as in name, the type of place you could work in all day, or meet your support worker, or friends or comrades.

For example, if you’d like to listen to a shocking tale on the antics of Giles Coren, revisit this Trashfuture podcast episode from 2019.

Free Palestine! Read about The Balfour Declaration.

Minsitry of Food leaflets via The 1940’s experiment. (If you don’t know me or my work, it’s worth mentioning I defintely don’t advocate for weight loss plans of this kind!)